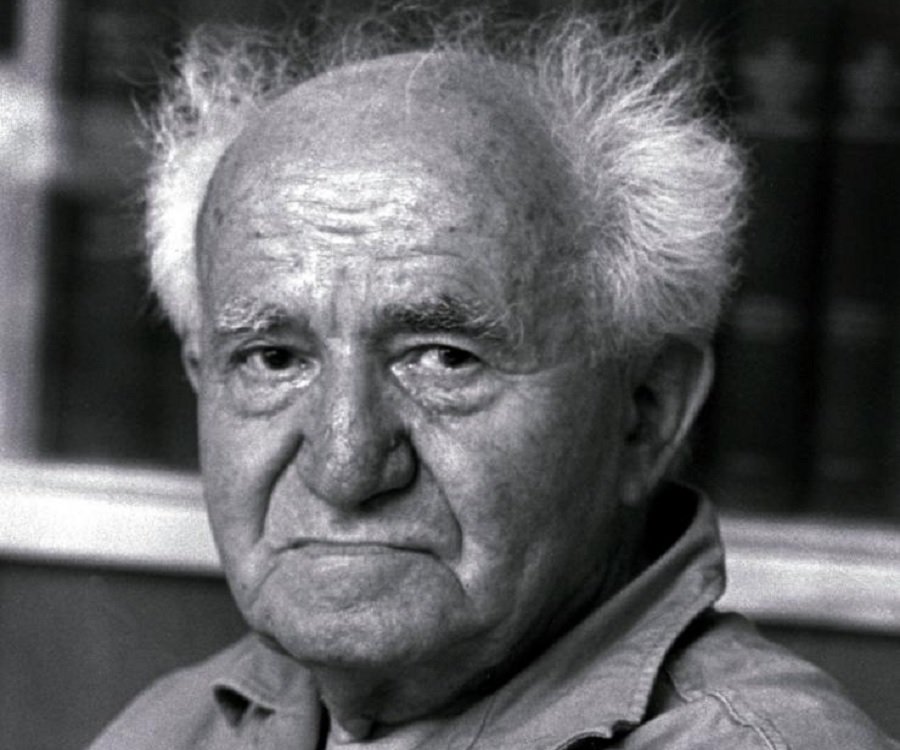

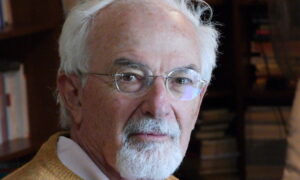

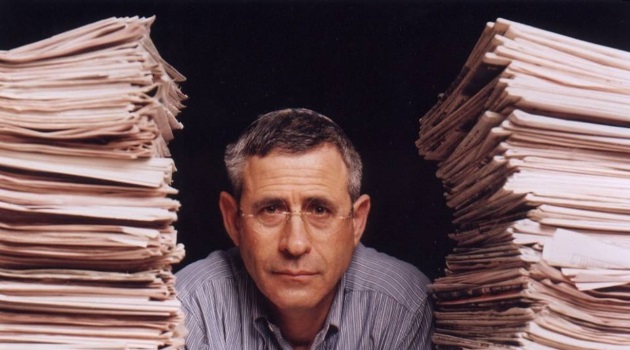

Today Benny Morris is one of the foremost experts of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Born in 1948, professor of history at the Ben Gurion University in the Negev, he has written seminal books about the topic that no serious scholar or researcher who is engaged professionally with the most controversial and lasting historical conflict of the planet, can avoid reading. Among them, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem 1947-1949 (1987), Righteous Victims (1999), One States Two States (2009).

His view of history is the clear and merciless view of an unrepentant realist who analyses and document facts with eyes completely dry.

We met in Jerusalem, in the neighborhood of Rehavia, in a bright day of the end of June.

When you started writing about the Arab-Israeli conflict you were hailed by the left as a scholar who was deconstructing the mainstream narrative of the Independence War. Then, the same admirers attacked you for what they considered a shift in your historical perspective. Was there actually a shift?

I have never shifted my historical perspective. I have always written what the documents have told me and the perspective did not change. If you look at my first book on the refugees ( The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem 1947-1949) you can see that the conclusions are exactly the same as those of the second version which came out sixteen years later. What changed was my assessment of Palestinian willingness to make peace with Israel. I was guardedly hopeful in the Nineties that Palestinians had shifted their position and that they were willing to make peace. It turned out that they were not. When they rejected the American and Israeli compromises in 2000, that changed my perspective. That is why a lot of people were angry with me, because I said that there is no peace not because of the Israelis but because of the Palestinians.

In 1922, Mussa Kazim al Husseini, the head of the Palestine Arab Executive said about Jews and Arabs, “Nature does not allow the creation of a spirit of cooperation between two people so different”. After ninety four years it seems that his words are still very actual. Do you agree with him?

Yes, it seems to me that he had it right. I don’t think that Jews and Arabs can live well in a state in which they could share power. I would say things have gotten worse, that the additional hundred years of animosity and violence have made them less trusting of each other then they were before. There has been terrorism, the refreshing of Arab insurgency, the siding of Palestinians with fundamentalism. All of this has made it even more unlikely that peace can be reached.

From your research it seems that you consider Arab rejectionism as having been from the beginning the main obstacle to any kind of resolution to the conflict. Is this so?

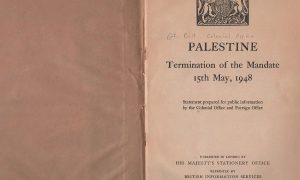

In my view Palestinian rejectionism has not changed. They said no to the compromise set forward by the British in the Thirties, they said no to the United Nation Partition plan which expressed the will of the international community, they said no in 2000 with Arafat at Camp David and they said again no with Abu Mazen as their leader in 2008 to the Olmert compromise. In the meantime Hamas has got much more stronger and oppose any type of territorial compromise. I think that the chance of a compromise is nowhere near the horizon.

I would like to talk about the attitude of Zionist leaders before and during the Independence war. There is one vexed question about the issue of transfer thinking by Zionist leaders both before and during the war. There are those who insist it was a product of pre-planning arriving to the extreme of accusing the Zionist leaders of genocidal mentality, and those like you according to which it was more the consequence of the threat posed by the Arabs to Jewish existence. What can you say about this?

Firstly it has nothing to do with genocide or genocidal mentality. At the worst some Israeli leaders thought in the terms of transfer, no one thought in terms of massacre and certainly not in terms of mass murder and in fact that didn’t happen. Palestinians launched a war against the Jews and the Israelis responded. In the 1930s as antisemitism increased in Europe, there was a need for a safe haven for the Jews. The United States and England and everyone else did not want to take in the Jews. The desire of the Jews was to come to Palestine were Jewish sovereignty had existed for centuries, and some leaders including Ben Gurion and Weizmann thought in terms of transfer of part of the Arab population or all of the population from the area in Palestine that was to become the Jewish state. Now, in 1937 the Peel Commission proposed to the Arabs a partition with the Jews getting 17% of Palestine and Arabs getting something as 70%. The Jews thought it was only fair if they were getting 17%, that at least it was going to be empty of Arabs so they would have space enough to absorb Jews coming from Germany where they were being persecuted. This is what the Peel Commission felt it was fair also. It recommended transfer as a prerequisite accompanying the two states solution.

Some Jews rejected the idea of transfer, as they thought there was something immoral in the idea of expelling part of the native population, but others thought that the morality of saving hundreds of thousands of Jewish lives superseded the immorality of throwing out several hundred thousands, two hundred twenty five thousands Arabs, from the area that would become the Jewish state. They were going to be moved from the area designated for the Jewish state to the Arab area. They were not going anywhere else, they were going to live among their own people and they were going to be compensated. That was the idea, it was the Peel Commission recommendation and it was endorsed by people such as Ben Gurion and Chaim Weizmann. The British governorate endorsed it but then reneged it, and in 1949 recommended that all of Palestine was to be handed over essentially to Arab sovereignty. Transfer occurred in 1947, 48 and 49 as a result of the war.

The Arabs of Palestine and afterwards the Arab states around attacked the Jews and the emerging Jewish state. It was a civil war in the first half in which the population was intermixed and the only way to win for the Arabs was to drive out the Jews from the areas that were becoming Arab and for the Jews to drive out the Arabs from the areas that were becoming Jewish. The Jews were more efficient and essentially drove out the Arabs. Most of them fled as a result and the Jews did not let them back. Some were expelled, some were also ordered or advised by their leaders to leave thinking that they were going to come back once the Arabs won the war. It did not happen and they did not come back.

Some Israeli historians unlike myself do not think that when Ben Gurion and Weizmann talked about transfer in the Thirties they were serious about it, on the contrary I think they considered it seriously but the British authorities didn’t carry it out and the Jews couldn’t carry it out in the Thirties, but there was serious thinking about the issue. In November 1947 when a partition of the country was proposed there were supposed to be four hundred thousand Arabs in the Jewish state and slightly more than five hundred thousand Jews and the Zionist leaders, including Ben Gurion and Weizmann, accepted this, that there was going to be a large Arab minority in the Jewish state. You could say that they were insincere, that they never meant it, but they said yes. Arabs said no and started shooting.

When I interviewed German scholar and political scientist, Matthias Kuntzel this fall, he emphasized that already during the Thirties the Muslim Brothers and Haji Amin al Husseini had Islamized the war against Zionism and the Jews. Would you agree with him that the strongest roots of the Arab-Israeli conflict are religious?

Not completely. The conflict combines elements of politics and national struggle within the two sides and also religious conflict. At different times one of the two prevails but indeed from the beginning there was a large religious element in Arab antagonism towards Zionism and it increased with Haji al Husseini. He was a cleric and understood very well that in order to mobilize the Arab masses you have to talk religion, not politics. At that time the masses did not know what nationalism was about but they understood what Allah was about and what the holy sites were about. Al Husseini said that the Jews wanted to take over the Temple Mount, that they wanted to destroy the mosques and this was accepted by the Arab masses and led them to bouts of violence against the Jewish presence and the emerging Jewish state.

There is a deep religious antagonism in Islam towards Judaism and it is anchored in the Koran as Judaism was a rival religion to Islam when Muhammad began preaching and in fact he destroyed a number of Jewish tribes. Religion is still the base for continuous Muslim antagonism towards Jews and Christians and a justification for jihad.

Today its common knowledge to call the Israeli presence in the West Bank, “occupation”, with all that this definition entails, however this definition is highly controversial and openly contested by Israel. As a matter of fact, legally, the territories are considered disputed. What is your position on this issue?

The territories are disputed for sure but there is also a semi-occupation. Why semi-occupation? Because some areas in the West Bank, especially those with a large Arab population are in some ways governed by the Palestinian Authority but they are also surrounded by Israeli road blocks and forces so there is some kind of occupation. So, if they want to go to Jordan or want to fly over to the States they have to get Israeli permission, if they want imports they have to come to Israel, if they want to export something it goes to Israel, if they want to build in certain areas they have to get Israeli permission. So it is a semi-occupation, it is an unusual occupation. Israel is not there but it controls the area around. The same applies to the Gaza Strip, it is under Hamas control completely but Israel controls the air space, the sea coast and some of the exits from the Strip and Egypt controls another exit south of it. Hamas rules inside, puts people in jail, kills opponents, imposes religious law upon them, this is also true, they govern in some way, they are sovereign in some way, but not completely because Israel is around them and supply them with electricity and water. They live off Israel basically.

In One States Two States you dismiss as completely unrealistic the idea of a binational state and write that “The two states idea remains the only sound moral and political basis for a solution offering a modicum of justice and trace a chance for peace for both people”. How much do the Palestinians really want such a solution?

I don’t think they do. As they did in the past consistently they don’t want a solution now as well. They want all of Palestine. They believe it’s all theirs in terms of justice. Dividing the land with Israel, having 78%, they consider this completely unjust and are not willing to accept it. Fatah, the so called secular movement, plays a game as if it is willing to have a two state solution, Hamas says no blackly, Abu Mazen wiggles around, doesn’t agree to a Jewish state next to a Palestinian state but says yes, however, when it comes down to negotiate, he certainly won’t sign any two state agreement, as Arafat didn’t and as Abu Mazen himself didn’t in 2008 when it was offered to him.

Let us say that finally there will be an agreement between the Israeli government and the Palestinian Authority. How seriously an eventual agreement could be taken in the face of the strong opposition of Hamas who rules over one million and five hundred thousand Gazans?

Hamas does not only rule over one million five hundred thousands Arabs in Gaza but it has a deep influence also in the West Bank and in refugees camps in Lebanon, Syria and Jordan. Hamas has a very strong support. I don’t believe that any Palestinian Authority leader, Abbas or his successor, will ever sign an agreement for it will be a dead warrant. Hamas will kill him, Hamas will subvert the agreement if he does sign it, but I think he will not sign it. Even if he does, as you suggest, Hamas will revolt and most Palestinians will bow to Hamas because they have been educated, inculcated with the belief that the Israeli are robbers and that their presence in Palestine is illegitimate, so they won’t agree to it. They believe that history is on their side. This is a problem, history being the surrounding Arab states, Arab economic power, Arab political power, the Muslim world, etc. The Jews are a little more than six millions in this small corner of the world where there are hundred millions Arabs, so the Arabs look at it objectively and say it cannot last, it is an anomaly. All that we need to do is not sign any agreement and eventually demography, economic power, political power will decide the result and it will end up like with the Crusaders who were kicked out in the 12th century.

Would you agree that the mainstream narrative according to which the Palestinians are victims and the Jews exploiters and persecutors is a reframing of the persistent anti-Semitic trope?

It’s a whole lot of things. Look, both people are victims. The Jews are victims of two thousand years of Christian and Muslim persecution and they are the victims of Arab attacks on them and of terrorism by Palestinians. The Arabs are victims in the sense that Israel drove out a large proportion of them from their homes, occupied land and made them live under a form of semi-occupation since 1967. The Jews at the moment in the Middle-East are the strongest but when you look at the map and the demographic reality, the economic reality, the political reality, the Jews are really the underdogs in historical terms. We are stronger than the Palestinians but the Arab world which is now fragmented is potentially much stronger than we are. I have called one of my books Righteous Victims because really both sides are victims and claim to be victims, but if you look at it in a historical perspective the Jews are the bigger victims even if in the immediate sense the Palestinians are also victims and they have every right to feel as such. However, their victimization is in large part of their own making because they were offered a state by the Peel Commission, by the United Nations, by Israel and they always said no. If they would have accepted they would not be victims, they would have a state of their own, true not all of Palestine, but they would have had a large part of it, or, as it was offered to them later, a small part of it, but in any case, a state. They are victims partially because they have kept saying no.

In the West the bias against Israel is very strong. Many consider it as a vestige of colonialism and this definition has been selling very well from the Sixties onwards. What you have to say about this?

The colonial paradigm refers to an imperial mother country that sends its children or sons to other lands, conquers them and then exploits the natives and the natural resources. Zionism was the project of a persecuted people in Europe, the Jews, who needed a homeland and came here and bought pieces of land. They didn’t conquer anything, the bought. They were not serving as agents of any empire, they thought they were serving as agents of their own people. It is true that Britain at first supported them for a while and then withdrew their support as it is also true that the United States supported them from a certain point on but they were never agents of America as you can see from the Obama/Netanyahu rivalry. It is true that in some sense Israel protects some American interests and Western interests in the area because we share the same values and so on. There is something colonial in Zionism in the sense that Zionism was an European movement and it is Europe moving to a Third World land and gradually taking it over. In this sense there is a colonial element. Zionism established what we call moshavots and settlements which gradually expanded inside Palestine from a few to more and more. So, again, in this sense it is a colonial movement, but in no sense to be compared to imperial or Western colonialism.

You are a stern realist. There is never a soft spot in what you write and say. It is too pessimistic to see the future of Israel as that of a perennial fortress in the Middle East, or is this just the soundest way to face reality?

I think that the reality in the Middle East and even more so after the so called Arab awakening, means that Israel, in order to survive here, and I am not sure it is going to survive, the Roman empire did not survive, no state survive forever, needs to be a fortress, needs to be strong. It has to repel Arab attacks and Arab antagonism and Western ill will, which is growing, as you say. Israel could behave better in certain ways, it could stop settlements, I have never supported the settlement enterprise, show the West that it is sincere in its will to peace. There are other gestures that the government could make. For example, building a port in Gaza that could be monitored internationally and by Israel. I am not saying it could be done, I am not saying this could work. The real basic problem is not really the Israeli gestures or policy but it is Arab rejectionism.

In this way we go back again to the main point.

Yes, that’s right, but is how things are.